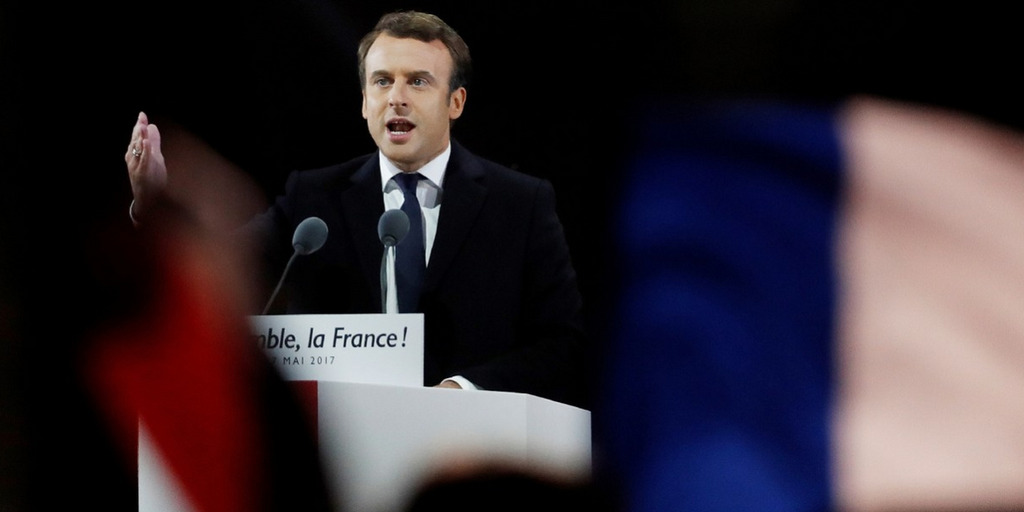

French Embassy in the U.S. / Flickr - CC BY NC 2.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

Macron's first 100 days: Convincing, but problems are already in sight

After a hard-fought election, many people in France are hoping that their new president will be able to unify the country. Tuesday marked Emmanuel Macron’s 100th day in office, and he is off to a convincing start – writes Prof. Henrik Uterwedde, our Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) expert for France. Yet a crucial test awaits Macron at summer’s end.

Is France entering a phase of fundamental change? Emmanuel Macron is off to a convincing start. Skillfully and purposefully, he is calling on policy makers and the public to endorse his reforms. One thing, however, has already become clear: Difficulties await at summer’s end.

The authors of this year’s Social Governance Indicators Report, published in August by the Bertelsmann Stiftung, wrote the following about France’s need for reform and its governance capacity shortly before the country’s presidential election: “France requires bold measures, including unequivocal and in some cases unpopular decisions. It also needs an open discussion of the country’s problems, along with more social dialogue and governance that is clear, consistent and coordinated.”

Against this background, President Macron’s first 100 days have been decidedly encouraging, since he clearly wants to overcome the country’s major structural hurdles. His reform agenda includes problems which have long been acknowledged and which have been documented in past SGI reports: bureaucracy, public debt, labor-market shortcomings, inadequate occupational training, ineffective social welfare programs, and outdated industrial relations. Macron is determined to get results – quickly.

The president’s chosen issues

The top priority is Macron’s very controversial effort to reform the labor code. The president wants to give businesses more freedom to adjust their human resources policies to reflect economic conditions. Companies are to be allowed to reach agreements on hiring, work schedules and compensation that deviate from industry norms. The president wants to make it easier for labor and management to negotiate with each other at individual businesses. He also wants to simplify the often lengthy and expensive lawsuits that inevitably occur when workers are laid off. In return, employees’ rights to occupational training are to be expanded, and unemployment benefits are to be increased.

France’s parliament completely supports the president’s effort to introduce legislative reform. That, in turn, has given Macron the freedom to carry out ongoing, intensive consultations with unions and trade associations and to react flexibly to their criticisms. Parliament is set to pass the planned legislation as early as September. In addition to its considerable economic importance, this reform is highly significant in political terms, since it is the litmus test for whether Macron can achieve policy goals that are unpopular, thereby truly changing the country.

The new government’s second focus has been on immediate measures to provide the unemployed with occupational training, and a reform of the vocational education system that is to be passed in 2018. The goal is to expand twin-track training for apprentices, i.e. training that takes place at both schools and businesses. This, too, is meant to address a sensitive point, namely that until now considerable barriers have existed preventing students who have completed their secondary education from entering the job market, something that has led to notoriously high youth unemployment rates in France.

Third, in order to send a hopeful signal to the country’s troubled suburban neighborhoods, the president is giving priority to hiring new teachers. The goal is to reduce by half the number of students in elementary-school classrooms in socially challenged areas.

A fourth issue is the country’s tax policies. Macron wants to ease the business community’s tax burden now and over the long term while aiding households with low and mid-level incomes. He has little room to maneuver, however, since the deficits left behind by President Hollande are much higher than previously assumed. In addition, Macron wants to reduce the country’s deficit to below 3 percent of GDP, the threshold mandated by the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact, in order to bolster France’s credibility vis-à-vis its European peers. This, however, has resulted in delays in realizing the promised tax cuts. In order to reassure the country’s economic players, the current draft of the 2018 budget scheduled for release in September clearly references the changes planned for France’s tax code during the entire legislative period, i.e. until 2022.

France is back in Europe

Since becoming president, Emmanuel Macron has used every opportunity to improve France’s standing on the international political stage, following the decline the country has suffered in recent years. His initiatives and public appearances have proven effective. Macron’s decidedly positive attitude toward European integration, which has overcome the country’s euroskepticism and its populist and nationalist tendencies, has generated high expectations within the European Union. His step-by-step method – first implementing national reforms to regain confidence in France’s stability and returning to a balanced budget, then generating support for further developing the European currency union – has met with approval in other European nations, above all in Germany. This has led to hopes that France and Germany will once again take on a strong leadership role within the EU.

Needed: determination and negotiating skills

Even if the president’s agenda is persuasive and his reforms target the country’s core problems, he needs political backing if he is to achieve them. What are his prospects here? From an institutional perspective, things look positive: Macron has a clear majority in parliament. In addition, according to the Fifth Republic’s constitution, the president and prime minister are empowered to effectively lead the government, to prescribe the guidelines individual ministers must follow in carrying out their work and to ensure that approved measures are effectively implemented by public administrators.

Politically the conditions are also favorable, since Macron has broken through the often ideologically set and therefore unproductive barriers polarizing the country into right- and left-wing camps, thereby winning broad support for his centrist course. With that he has been able to bring together more moderate reform-minded forces on both the left and the right to create a coalition that endorses reform. Hollande often failed to reach his policy goals because of lack of support from his own Socialist Party. Macron, however, founded his own movement, La République en Marche (The Republic on the Move), in 2016 and until now it has completely backed his reform agenda. Macron wants to act quickly since it takes time for reforms to make themselves felt.

The considerable support Macron initially received has begun to falter, however, now that the details of his reforms and his budget policy have been made known. Although Macron plays a very dominant role within his movement, the movement itself and its parliamentary representatives are relatively weak, a combination that has been criticized as having led to an excessive concentration of power. In addition, the president faces France’s traditionally strong forces of social resistance and the widespread and often aggressive aversion to any type of economic deregulation. In the past, the trade unions have repeatedly organized major demonstrations to protest such deregulatory efforts and they have threatened to take action in September if parliament approves the planned labor-market reforms. That is another reason why Macron is in a hurry to engage business organizations and labor representatives in a strategic dialogue, thereby including them in the policy debate. He wants to take advantage of the fact that some union members are clearly willing to accept change. The first round of in-depth negotiations with each of the eight most important business and labor groups ended in July. Macron will need determination and all of his negotiating skills if he is to pass this first acid test of labor-market reform. Only then can the world be sure that France is truly on the move.

Prof. Henrik Uterwedde is an associate researcher at dfi, the Franco-German Institute in Ludwigsburg, and our SGI country expert for France.